Seizures

Seizures are the clinical manifestations of transient, uncontrolled electrical activity between brain cells. They cause changes in behaviour, consciousness, motor activity, sensory perception and/or autonomic functions. All nervous tissue has a threshold of excitability. When this threshold falls below a critical level, spontaneous neuronal depolarization occurs. If a large enough number of neurons are involved, it will cause a wave of depolarization in an entire area (partial seizures) or in the entire nervous system (generalized seizures).

Seizures are always a sign of abnormal brain function that can be either primary (intracranial) or secondary (extracranial). Tests may be helpful in extracranial aetiologies, which are the causes described in this fact sheet.

Epilepsy involves primary, recurrent seizures. Metabolic disturbances can also cause seizures.

Symptoms

In small animals, most seizures manifest as generalized tonic-clonic seizures. In the case of partial seizures, only one part of the body is involved and the animal will manifest abnormal behaviour (aggression, hallucinations, etc.).

Seizures can be divided into three phases: the preictal or aura phase, when the animal may exhibit strange behaviour (hypersalivation, licking, hiding), the ictal phase or the seizure itself, and the postictal or recovery phase, when the animal may be tired and disoriented. The postictal phase does not usually occur in non-epileptic seizures

Owners often only become aware of the seizure when the animal is in the postictal phase (i.e., they do not observe the actual seizure). Therefore, it is important to take a comprehensive history in order to confirm that the animal has really had a seizure. The history should include the pedigree, vaccinations, travel, contact with other animals, stress, heat phase if female, trauma, access to the outside (toxins), previous clinical history, previous medications, form of onset of seizures, interictal periods, aura, seizure and post-seizure and description of any abnormality (day, time, duration, and characteristics). A complete neurological examination should be performed after the postictal phase, since the results of such an examination during and immediately after the seizures could be misleading. The findings of the examination and the description of the symptoms will indicate which tests are required.

The neurological examination should assess the animal’s mental status, gait, standing posture, cranial nerves (pupils, vestibular responses, threat reflexes), postural reactions (proprioception, jumping, etc.), spinal reflexes, and pain perception.

Extracranial origin

- Toxic:

Poisons and/or chemicals such as strychnine, ethylene glycol, metaldehyde, organochlorines, lead. - Metabolic:

- Hypoglucaemia: Symptoms after exercise. The animal may fluctuate between states of hyperexcitability and irritability and lethargy and depression, and may also present muscle spasms (facial) and fainting.

- Hypocalcaemia: Lactating females. Associated with nervousness, tetany, muscle spasms (face and ears) in dogs, and lethargy, anorexia, forced breathing and facial rubbing in cats.

- Hyperlipidaemia: Due to an increase in lipoproteins and/or triglycerides.

- Hyperviscosity: Multiple myeloma – Congestion of mucous membranes (purple appearance) and retinal vessels, epistaxis, tendency to bleeding and nonspecific CNS symptoms, musculoskeletal symptoms system such as lameness, fractures, joint pain, etc.

- Diabetes – Diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolarity.

- Electrolyte imbalances – Hypercalcaemia (gastrointestinal and kidney dysfunction, arrhythmia, as well as weakness, hyporeflexia and depression); Hyponatraemia (cerebral oedema); Hypernatraemia (cellular dehydration). Both excess and depletion of sodium causes weakness and depression.

- Hypothyroidism - In cats aged over 5 years.

- Thiamine deficiencies – In cats, depending on diet.

- Degenerative processes – Metabolic thesaurosis affecting young animals.

- Hepatic encephalopathy – Given its importance and complexity, it is described in a separate fact sheet together with uraemic encephalopathy.

- Inflammatory/infectious diseases:

Distemper, FIP, toxoplasmosis, leukaemia and feline immunodeficiency. - Epilepsy:

- Acquired. The brain is permanently injured due to internal or external factors.

- Idiopathic. Far more frequent in dogs than in cats. No specific symptoms.

Interpretation of laboratory tests

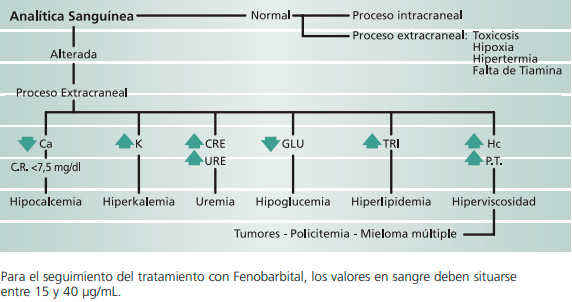

- Normal blood test, biochemistry and urinalysis:

Intracranial pathology – Epilepsy (idiopathic or acquired), vasculopathy, congenital malformation, trauma.

Extracranial process – Toxins; thiamine deficiency; hyperthermia and hypoxia. - Abnormal blood test, biochemistry and urinalysis:

Indicates an extracranial pathology.

The tests will identify different abnormalities depending on the aetiology of the disease.

Bibliography

- CAUZINILLE, L. (1998) Pratique Médicale et Chirurgicale de l’Animal de Compagnie., vol 33, 85-88.

- DELGADO, P.T. (1998) Pequeños Animales Año III, nº 12, (5-14).

- ETTINGER, S.J. (1995) Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th) W.B.Saunders. 152-156. JAGGY, A. (1998) Journal of Small Animal Practice. vol. 39, 23-29.

- KLINE. K.L. (1998) Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice. Vol 13, nº 3, August. pg. 152–158. KNOWLES, K. (1998) Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice. Vol 13, nº 3, August. pg.144-151.

- NELSON, R.W (1995) Pilares de Medicina Interna en Animales Pequeños (Intermédica). 584, 705-715.

- O’BRIEN, D. (1998) Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice. Vol 13, nº 3, August. pg. 159-166.

- OLIVER, J.E. (1997) Handbook of Veterinary Neurology (3rd.) W.B.Saunders. 313-325

- PARENT, J.M.L. (1994) Seizures in cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. Vol 26, nº 4. pg 811-825.

- PODELL,M. (1994) Seizures in dogs. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice Vol 26, nº 4. pg 779-805.

- SHELL, L.G. (1998) Veterinary Medicine June. 541 – 552.

- SODIKOFF, C.H. (1996) Pruebas diagnósticas y de laboratorio en las enfermedades de los pequeños animales (Mosby) 134-135,154,156-159.

- TENNANT, B. (1994) Small Animal Formulary (BSAVA). 44, 119-121,124, 131, 132, 165.

- THOMAS. W.B. (1998) Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice. Vol 13, nº 3, August. pg. 167-178.

- WHEELER, S.J. (1989) Manual of Small Animal Neurology (BSAVA). 52, 119-124

Clinical record

Seizures

Recommended tests

For the handling of samples, please consult the Uranolab® catalog.

- Complete Blood Count

- Proteinogram

- Blood Biochemistry: AMI, BIT, COL, CRE, ALP, GLU, GOT, ALT, PT, TRI, URE, CAL, P, Na, and K.

- Urinalysis: Biochemistry and Sediment

Tests will be conducted based on the suspected etiology.

- Suspected poisoning: Contact the Laboratory.

- Suspected infectious disease (Distemper, FIP, Toxoplasmosis, Ehrlichiosis, etc.). Perform serological titration or detection of the etiological agent.

You can request the necessary tests from Uranolab® through our website; you just need to register your clinic with us.

Discover moreOther clinical records

Companion animals are our passion, and our job is to listen to you in order to offer you innovative products and services and contribute to improving the quality of life of pets.

SEE ALL